Why folks keep after native economies collapse − a narrative of residence among the many ghosts of shuttered metal mills

by Tracy Walsh

The Dialog

It was noon on a Saturday, and Simonetta led me from the open entrance door of her residence in southeast Chicago to her sitting room and settled subsequent to her husband, Christopher, on the sofa.

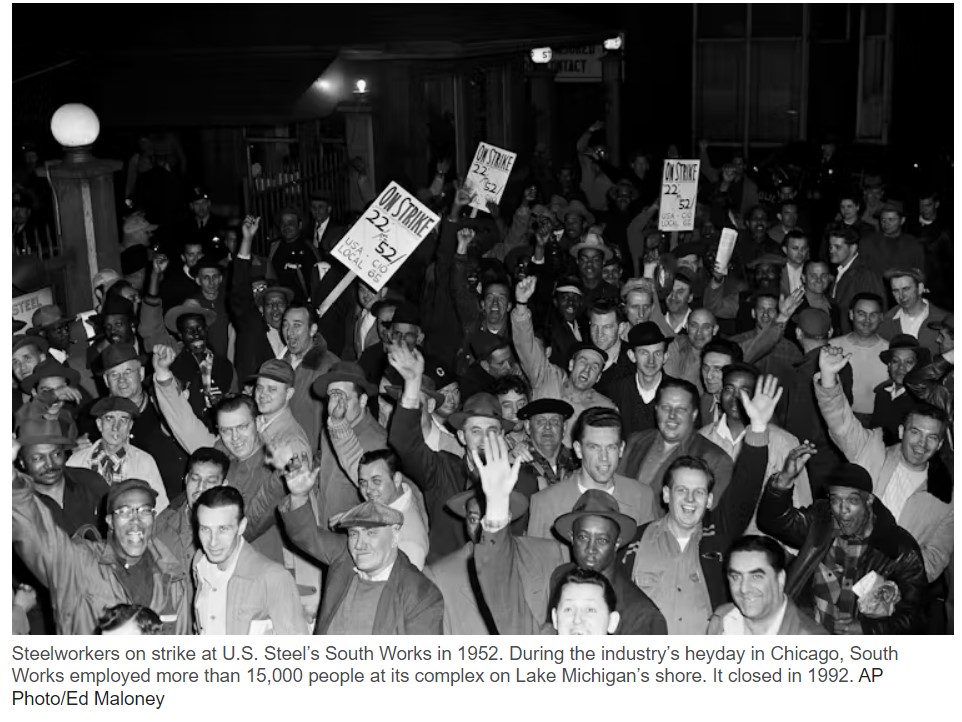

Within the Eighties, Christopher had labored a couple of blocks away at U.S. Metal South Works, incomes thrice the minimal wage with a highschool diploma – greater than sufficient to purchase a home close to Simonetta’s dad and mom earlier than their first child arrived. Like their neighbors in southeast Chicago, Simonetta and Christopher’s expectations for work and residential have been set by the metal business.

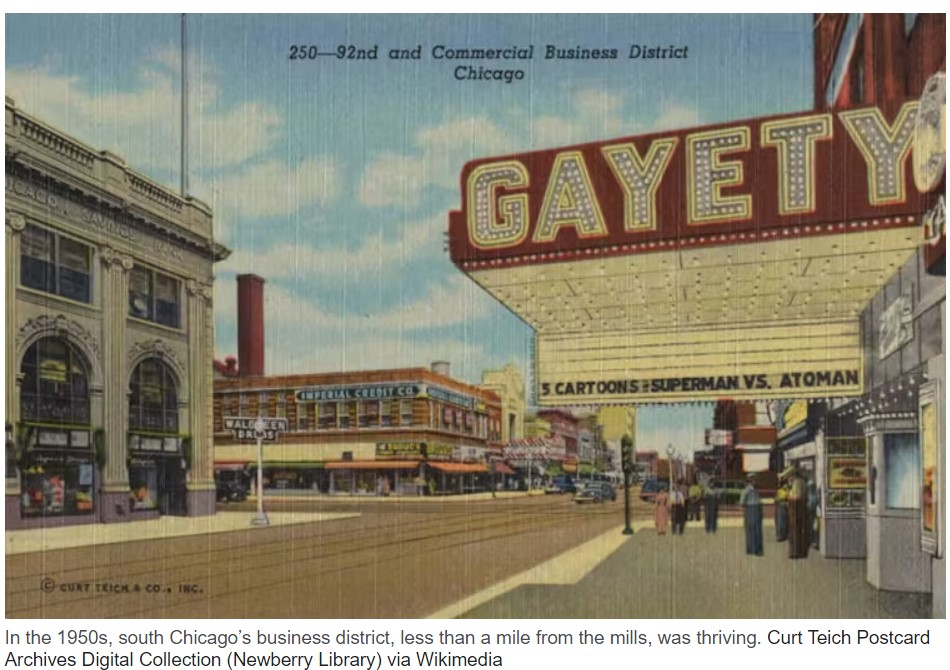

Between 1875 and 1990, the employment supplied right here by eight metal mills created a dense community of working-class neighborhoods on the marshlands 15 miles south of downtown Chicago. For the tens of 1000’s of staff who lived and labored on this area, metal was a uncommon breed of labor: unionized, blue-collar jobs that paid middle-class wages, with beginning salaries within the Sixties at almost thrice the minimal wage.

Alternatives for promotion, advantages and safe job tenure allowed employees to purchase homes, store at native shops and put away financial savings. The metal business was greater than simply work; it organized the spatial and social relations of this neighborhood.

Its collapse was devastating to folks dwelling within the neighborhood, Simonetta instructed me. As mill after mill shuttered within the final 20 years of the Twentieth century, folks started to depart to seek out new work – principally service jobs – situated removed from southeast Chicago’s financial melancholy.

As we stared on the silent road, I requested them, “Why did you stay?”

Christopher paused, then mentioned merely, “We had the building.” The couple owned their three-story row residence outright after many years of paying off the mortgage. Certain, it had some crumbling corners and the roof sagged, but it surely was theirs. These 4 partitions remained strong throughout and after the topsy-turvy years of financial collapse. Greater than only a type of fairness or materials house, this constructing was the muse for his or her stability.

Why do folks keep in laborious locations?

For the previous 10 years, I’ve requested why folks keep when their native economic system collapses.

In my 2024 e book, “Who We Are Is Where We Are: Making Home in the American Rust Belt,” I used ethnographic analysis and interviews to review the long-term outcomes of deindustrialization in a rural iron-mining neighborhood in Wisconsin and concrete manufacturing neighborhoods set amid the metal mills of Chicago.

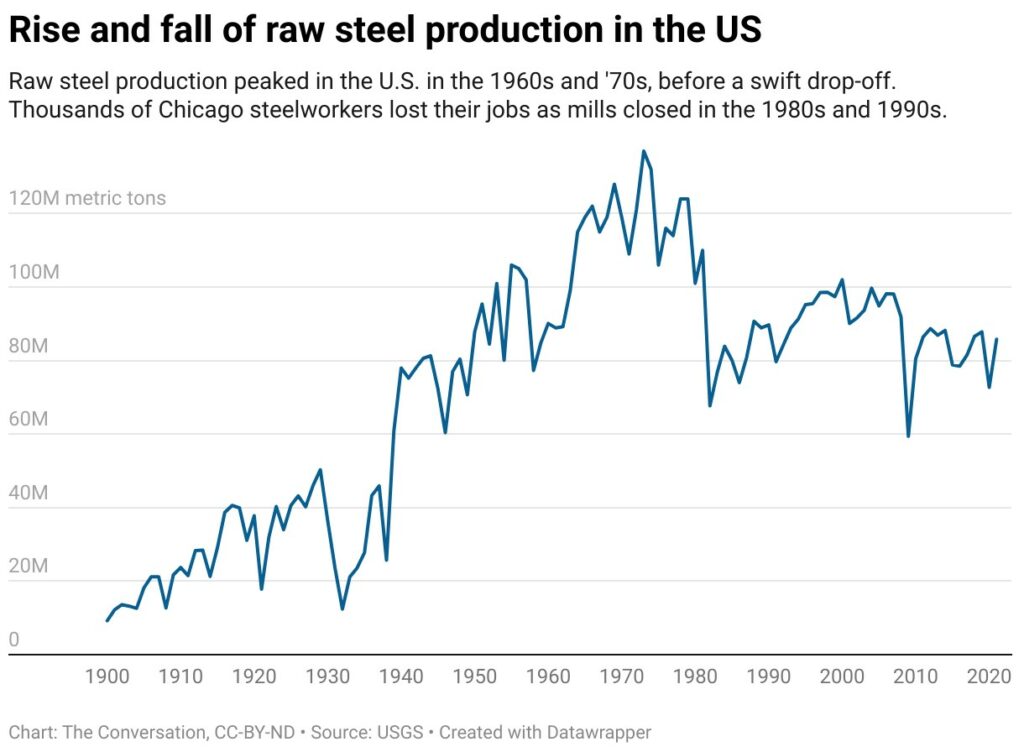

The causes of deindustrialization have been macroeconomic and international – technological change, commerce offers, environmental laws and elevated competitors – however the results have been native. Within the second half of the Twentieth century, cities and cities that grew up round industries that extracted iron and manufactured metal all of the sudden misplaced the core of their blue-collar employment.

Stretching from New York to Minnesota, the Rust Belt area has skilled 5 many years of almost double-digit unemployment charges. Within the wake of business closures, a whole lot of 1000’s of unemployed folks packed up their homes and sought their fortunes in factories or mines within the American South, or anyplace that wasn’t collapsing from financial melancholy. Within the course of, these deindustrialized locations not solely misplaced their grip on their residents however their place within the American story of financial progress, development and resilience.

However not everybody leaves.

For this analysis, I talked with greater than 100 folks, like Simonetta and Christopher, to know why folks keep in these neighborhoods as jobs dry up and shops shut. Many times, they argued that their stuckness in place supplied them stability in a chaotic world.

Homeownership: A lure and a technique to keep

The folks I spoke with usually started their tales with a sensible – and financial – concern: the funds and freedoms of homeownership.

For a lot of long-term residents, shifting elsewhere was economically not possible. Depressed housing values meant they couldn’t recoup their investments by promoting, and the method of shifting is itself costly. But additionally they argued that proudly owning their home supplied them a bit piece of stability within the early years of unemployment.

Within the mid-Twentieth century, good wages mixed with federally backed residence loans opened avenues of homeownership for blue-collar iron and steelworkers.

Starting within the Sixties, southeast Chicago transitioned from a majority rental neighborhood to at least one the place between 60% and 70% of homes have been owner-occupied. For Christopher, Simonetta and 1000’s of their neighbors, shopping for a house was a sound monetary resolution and a path towards attaining the American middle-class purpose of constructing wealth via personal property possession.

In fact, homes are greater than merely materials investments. Simonetta and Christopher’s home was additionally their household story. Within the first half of the Twentieth century, Simonetta’s dad and mom had immigrated from Mexico. Christopher’s grandparents had arrived from Mexico on the flip of the Twentieth century. Simonetta defined that since they’d grown up within the neighborhood, once they bought married, they needed to purchase a spot inside strolling distance of their dad and mom and webs of aunts, uncles and cousins.

Once they made the down fee in 1980, they benefited from plummeting home costs. Wisconsin Metal had simply closed its close by mill, and housing costs in close by neighborhoods had already dropped by 9%. However they hadn’t anticipated the entire area’s housing bubble to pop.

Housing costs of their neighborhood started to fall as U.S. Metal slowly laid off employees via the Eighties and Nineties. Even at the moment, the median worth of houses listed in southeast Chicago ranges from $80,000–100,000, lower than a 3rd of Chicago’s median of $330,000. When the neighboring mill closed, their household networks have been caught.

Simonetta recalled, “My father, my parents still lived in the neighborhood. They weren’t going anywhere. Where were they going to go?” She continued, “It’s not like we’re rich. I mean, the mill’s closed. We were unemployed!”

Even when their dad and mom needed to promote their home and begin a brand new life in a extra promising location, promoting within the financial free fall of deindustrialization would have price them an excessive amount of. Mass unemployment turned houses that have been as soon as sound monetary investments into almost unsellable liabilities.

What’s gained from staying at residence?

Even whereas the economics of homeownership restricted choices, proudly owning property was additionally a haven when every part else was in turmoil. Having “the building,” as Christopher known as their home, made their path ahead easy: Put meals on the desk by doing odd jobs and commuting an hour-plus to the suburbs, and look out for one another.

Dwelling can be the place household, socially constructed identities and acquainted experiences coalesce. The folks I spoke with drove me to their favourite lakes and parks, sketched maps to their beloved outlets or climbing paths, and identified historic markers of business pasts. They celebrated the social networks that also anchored their identities in place – prolonged household, annual parades and common college and work reunions.

Interviewees have been fast to confess that the sprawling disaster of deindustrialization constrained decisions and restricted their choices. However throughout the fractured scaffolding of postindustrial social life, a technology of long-term residents nonetheless belong to at least one one other.

“We survived, and that’s why we didn’t leave,” Simonetta mentioned. “The community has changed, but where else are we going to go? I mean, we’ve been here for fifty-something years. … This is my neighborhood.”

“That’s how you destroy neighborhoods,” Christopher interjected, “by leaving!”

Why folks keep after native economies collapse − a narrative of residence among the many ghosts of shuttered metal mills, The Dialog.com.