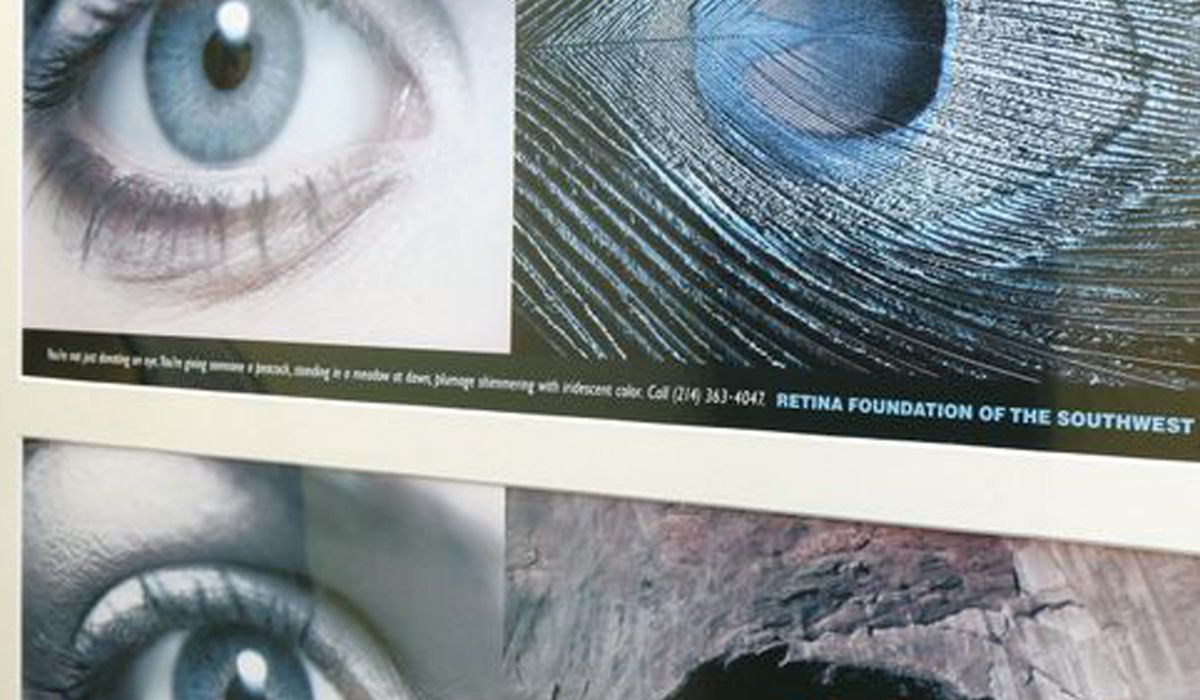

Doctors for the first time have partially restored the vision of a blind patient using gene therapy to inject a genetically engineered virus into his eye.

Researchers performed the therapy on a 58-year-old man who was diagnosed 40 years ago with an inherited eye disease called retinitis pigmentosa, which is loss of vision due to a breakdown and loss of cells in the retina.

The optogenetics therapy, which involves controlling nerve cells via light, allowed the patient to pinpoint objects including a notebook, small staple box and tumbler he couldn’t see before when wearing light-stimulating goggles, according to the study published Monday in Nature Medicine.

The researchers, who hail from University of Pittsburgh and various institutions in London, Paris and Switzerland, injected the patient’s worst-seeing eye with an adeno-associated viral vector to deliver a gene into the retinal ganglion cells — cells that are sensitive to red light.

The researchers said they opted for red light because it is safer and causes less pupil constriction than blue light used to activate many other sensors. In order to see, the patient had to also wear light-stimulating goggles, which capture images from the visual world using a camera that detects changes in intensity as distinct events, they said. The light then changes into monochromatic (of a single wavelength) images that are projected in real time as light pulses onto re-engineered cells in the retina.

Before the viral injection, the patient was unable to visually detect any objects with or without the goggles or without the goggles after injection, according to the researchers. But with the injection and goggles, the patient was able to perceive, locate, count and touch different objects using the treated eye while wearing the goggles, the study says.

“In the stimulated monocular condition but not in the natural binocular condition, the patient spontaneously reported identifying crosswalks and he could count the number of white stripes. Subsequently, the patient testified to a major improvement in daily visual activities, such as detecting a plate, mug or phone, finding a piece of furniture in a room or detecting a door in a corridor but only when using the goggles,” the researchers wrote in their study. “Thus, treatment by the combination of an optogenetic vector with light-stimulating goggles led to a level of visual recovery in this patient that was likely to be of meaningful benefit in daily life.”

An estimated 1 in 4,000 people worldwide live with retinitis pigmentosa, the National Eye Institute says. The condition is caused by mutations in more than 71 different genes, according to the Retinal Information Network, and there is no approved therapy for it. Difficulty seeing at night and a loss of side (peripheral) vision are common symptoms of the disease.

The study’s patient underwent eye exams both before and after injection. He was monitored during 15 visits spanning 84 weeks. There was no damage to his treated eye, which retained light perception beyond the 84 weeks of testing, the researchers noted.

“Only a decade ago, genetic testing and therapy for patients with inherited retinal diseases was typically a research exercise, but today, the field has given eye care providers an unprecedented ability to target some of these rare, sight-threatening diseases and potentially stem patients’ vision loss,” said Dr. William T. Reynolds, president of the American Optometric Association, who was not involved in the study. “While this specific study is limited to one patient, if reproducible, it would be an incredible development for patients and the medical community.”

The study is part of the larger PIONEER clinical trial to study the safety of the injection of adeno-associated viral vector paired with the light-stimulating goggles on patients with vision loss. Seven patients had received a single injection in their worst-seeing eye as of the end of last year. Due to COVID-19, only the 58-year-old male patient could participate in post-injection training sessions. The pandemic has disrupted the trial and prevented evaluation of the combined therapy for other treated patients, the researchers said.

However, the researchers are striving to start training other patients as the pandemic becomes more manageable with an estimated trial completion date in December 2025, CNET reported.

Dr. Raj Maturi, clinical spokesperson for the American Academy of Ophthalmology, said while the surgical technology for the procedure has been well-tested, the biggest hurdle will be finding the right patients who have significant retinal disease for the treatment.

Although the usual pathway to help those with rare diseases is direct replacement of the gene, Dr. Maturi noted that can’t always be done like the case with the study’s patients whose entire photoreceptor layer of the retina has been “compromised.”

“What helped him was that the ganglion cell layer at the top was replaced by these genes so it will give a very atypical form of vision, but they can do a few things for sure,” he said. “This is an extremely exciting time to be in ophthalmology. It’s an extremely exciting time to be in technology of this nature where it’s using a completely foreign gene to help human beings to do something that they lost.”

Health, The New York Today