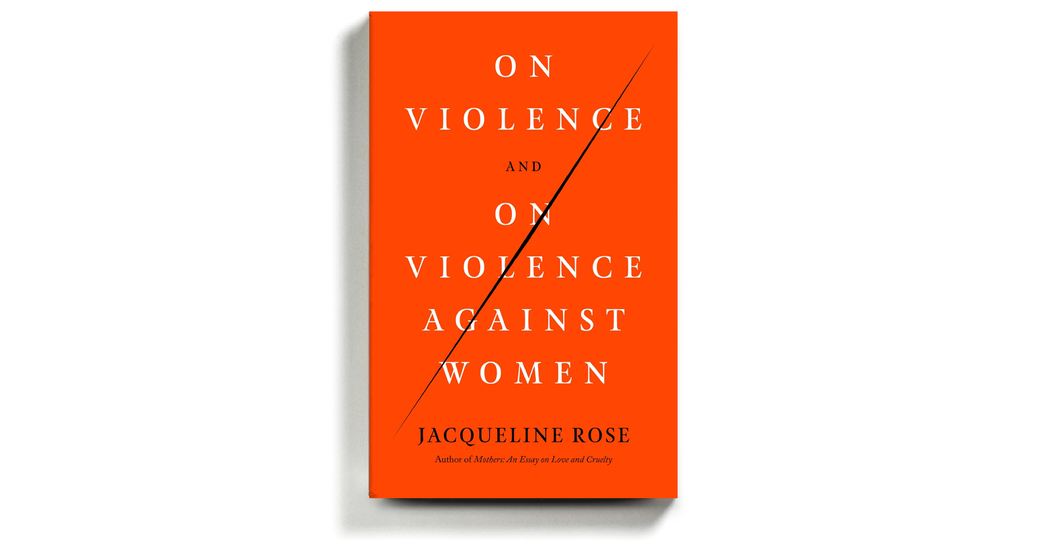

“Victimhood is something that happens, but when you turn it into an identity you’re psychically and politically finished,” she has said.

Rose roves widely in this book. She considers sexual harassment, Harvey Weinstein, student protests in South Africa, depictions of violence in contemporary fiction. Her centerpiece essay, on the murder trial of Oscar Pistorius, weaves in disability politics, South African gun culture, apartheid-era architecture, the shower scene in “Psycho” and, again, the price others must pay for our belief in our own innocence. (“Expelling dirt is as self-defeating as it is murderous. Someone — a race, a sex — has to take the rap.”) She returns frequently to violence’s encroachment on the inner life of the victim. “Harassment is always a sexual demand, but it also carries a more sinister and pathetic injunction: ‘You will think about me,’” she writes. In a close reading of Anna Burns’s Booker Prize-winning novel, “Milkman,” Rose quotes the protagonist, who is being stalked by an older man. “My inner world had gone away,” the girl says.

It is an incalculable loss, this theft of mental freedom. Rose cites the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein’s beautiful concept of “epistemophilia.” The infant’s strongest impulse, our native impulse, is to know.

For all that Rose reveals, her book might be most intriguing in its strictures and refusals. She will not, for example, list examples of atrocities — “feminism is not served by turning violence into a litany” — or add to the spectacle. She shies away from cheap pathos and struggles to avoid turning victims into figures of timeless suffering and “raw pity,” thereby obfuscating “human agency, the historical choices and willful political decisions.” What does it mean to report on violence, she asks, when it only “itches” the consciences, offers titillation or, worse, spurs support for the perpetrator? Donald Trump, Rose writes, “was adulated in direct proportion to the wrong which he clearly could do.”

These questions aren’t purely ethical. Rose searches for the modes that allow us to think more clearly and creatively. Literature becomes critical: “It is for me one of the chief means through which the experience of violence can be told in ways that defy both the discourse of politicians and the defenses of thought.” Unspeakable violations force new words and forms into being: Toni Morrison’s concept of “rememory”; what Burns in “Milkman” calls “numbance”; the broken, nursery rhyme horror-patter of Eimear McBride’s novel “A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing.”

For all her attraction to unruliness, Rose’s own sentences are cool, almost enameled in their polish and control. It’s in the movement of her prose, the way she seizes and furiously unravels ideas from her previous books, that we see the vigor and precision of her mind, the work of thinking, of forging new pathways that she holds up as rejoinder to the muteness of violence.