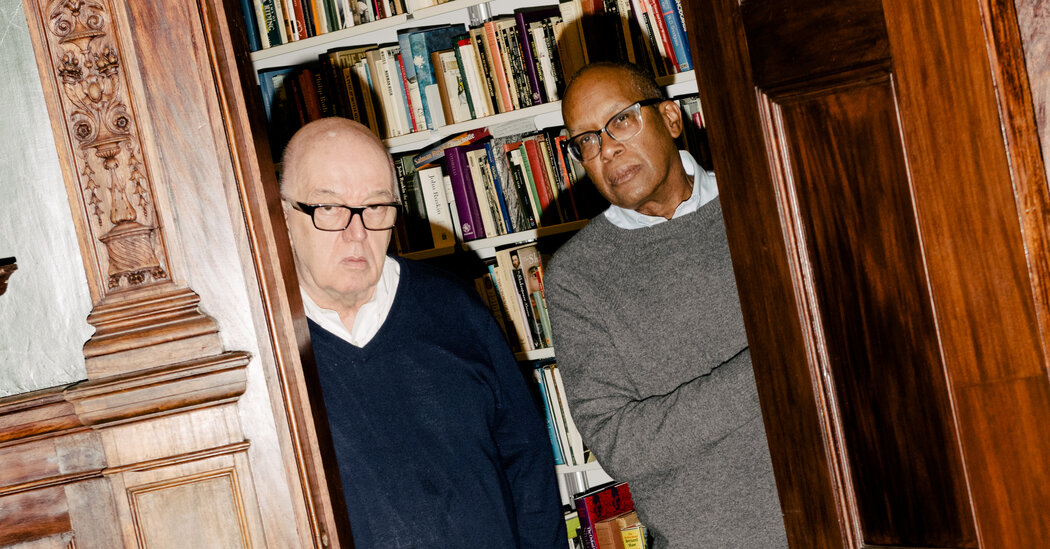

On a recent Sunday, they gave a tour of what has become a wonderland: gleaming wood paneling in the oval rooms, and faux bois and faux porphyry, where the paneling was stripped off; a glittering gold leaf and lapis blue frieze in the front hall; rooms painted in rich, tropical colors and a library bursting with more than 10,000 books in which you will find the complete diaries of Samuel Pepys, among other treasures. That afternoon, on the bottom edge of a linen curtain that was pooling on the rug, sat a fat tabby named Alex.

“Welcome to Jamesland,” Mr. Pinckney said. “It is always an adventure. He can’t help himself. I just sit back and watch things transform.”

In the Beginning

A former war reporter, foreign correspondent, theater critic and librettist, among other exploits, the Oxford-educated Mr. Fenton is also a scholar of architecture and interior design. He can declaim, slowly and with great precision, about the visual idiom of seemingly any architectural period. He knows what a dado is.

He also has a long habit of courting danger, domestic and otherwise. When Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese in 1975, Mr. Fenton, a stringer for The Washington Post and other papers, hitched a ride into the city on one of the conquering tanks. In the 1980s, on an expedition in Borneo with the British adventurer Redmond O’Hanlon, he nearly drowned in a river.

“James is a Renaissance man,” said Martin Amis, a friend since college. (With Christopher Hitchens, the late cultural gadfly, Mr. Amis and Mr. Fenton were once a fierce literary trio, employed in the 1970s by The New Statesman, the progressive British political and culture magazine.)

“I couldn’t be less of an expert on this kind of thing, but he just puts his mind to it,” Mr. Amis said. “Clearly what stimulates him is an absolute challenge.”