Gurnah began by writing recollections of his homeland and other snippets without ever intending to publish them, but over the years, stories started to take shape. What began as private reflections later struck him as part of a larger, more universal story, about “the way in which colonialism transformed everything in the world, and people who are living through it are still processing that experience and some of its wounds,” he said.

The same themes that occupied him early in his career, when he was processing the effects of his own displacement, feel equally urgent today, he said, as both Europe and America have been gripped with a backlash against immigrants and refugees, and political instability and war have driven more people from their home countries. “It’s a kind of meanness and miserliness on the part of these prosperous countries that say, we don’t want these people,” he said. “They’re getting these literally handfuls of people compared to European migrations.”

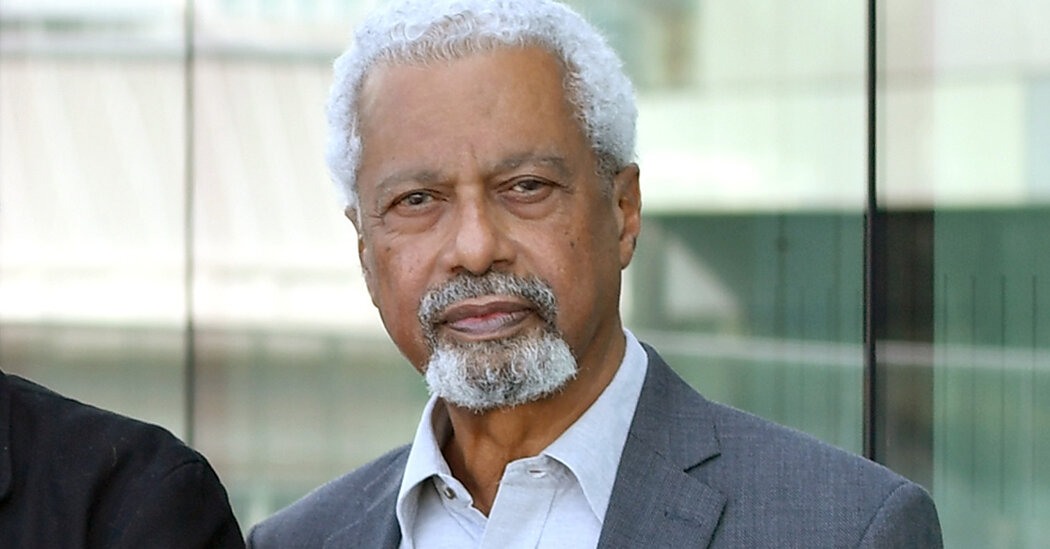

The news of his Nobel was celebrated by fellow novelists and academics who say that his work deserves a wider audience.

The novelist Maaza Mengiste described Gurnah’s prose as being “like a gentle blade slowly moving in.” “His sentences are deceptively soft, but the cumulative force for me felt like a sledgehammer,” she said.

“He has written work that is absolutely unflinching and yet at the same time completely compassionate and full of heart for people of East Africa,” she said. “He is writing stories that are often quiet stories of people who aren’t heard, but there’s an insistence there that we listen.”

Laura Winters, writing in The New York Times in 1996, called “Paradise” “a shimmering, oblique coming-of-age fable,” adding that “Admiring Silence” was a work that “skillfully depicts the agony of a man caught between two cultures, each of which would disown him for his links to the other.” But despite being hailed as “one of Africa’s greatest living writers” by the scholar Giles Foden, Gurnah’s books have rarely received the kind of commercial reception that some previous laureates have.

In the prelude to this year’s award, the literature prize was called out for lacking diversity among its winners. The journalist Greta Thurfjell, writing in Dagens Nyheter, a Swedish newspaper, noted that 95 of the 117 past Nobel laureates were from Europe or North America, and that only 16 winners had been women. “Can it really continue like that?” she asked.