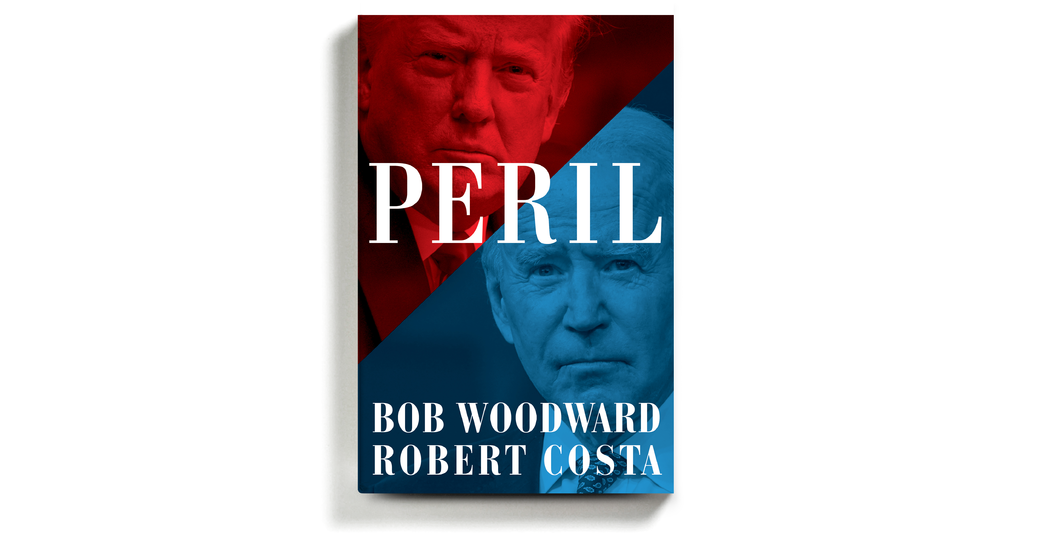

The titles of Bob Woodward’s three books about the Trump administration — “Fear,” “Rage” and now “Peril” — are appropriately blunt. The books, about the staccato stream of events that accompanied Donald Trump’s time in office, are written at a mostly staccato clip.

The frantic pace is redoubled in “Peril,” written with Robert Costa, Woodward’s colleague at The Washington Post. Broken up into 72 short chapters, it hurtles through the past two years of dizzying news. But while it covers the 2020 campaign season and the course of the pandemic and the protests after George Floyd’s murder and the opening months of Joseph Biden’s presidency, the book’s centerpiece is the riot at the Capitol on Jan. 6, and its primary concern is how President Trump behaved in the lead-up to and the aftermath of that crisis.

Books in this genre like to make news, and this one doesn’t waste any time. Its opening pages recount how last October and again in January, after the riot, Gen. Mark A. Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, had secret conversations with his Chinese counterparts to assure them that the United States was “100 percent steady,” despite what they might be seeing and hearing. “Everything’s fine,” he told them, “but democracy can be sloppy sometimes.”

The Chinese were concerned that Trump might lash out on a global scale in a desperate attempt to secure his power. Milley went over the process for nuclear strikes and other acts of war with his colleagues, to make sure nothing was instigated without his awareness. He was, Woodward and Costa write, “overseeing the mobilization of America’s national security state without the knowledge of the American people or the rest of the world.”

The authors then go back to begin charting the path to the extraordinary events of Jan. 6, alternating between Republicans’ attempts to corral Trump’s most outlandish behavior and scenes of Biden weighing whether to enter the 2020 race.

The day after the election, speaking to Kellyanne Conway, Trump “seemed ready, at least privately, to acknowledge defeat.”

Enter Rudy Giuliani.

The former New York mayor becomes a more prominent player here than in the previous books. (One especially brutal set of consecutive entries for him in the index reads: “hair dye incident,” “hospitalized with coronavirus.”)

In “Fear,” Woodward had noted that Giuliani was the only Trump campaigner to appear on a prominent Sunday morning talk show to support his candidate the week that the notorious “Access Hollywood” tape was leaked. He actually went on five shows, a rare feat. At the end, Woodward wrote, he was “exhausted, practically bled out,” but had “proved his devotion and friendship.” His reward? “Rudy, you’re a baby!” Trump reportedly yelled at him in front of staffers on a plane later that day. “I’ve never seen a worse defense of me in my life. They took your diaper off right there. You’re like a little baby that needed to be changed. When are you going to be a man?”

It will be left to psychologists, not historians, to write the definitive account of why Giuliani remained so steadfast to the president, but in “Peril” he’s portrayed as the prime force behind Trump’s refusal to let the election go.

“I have eight affidavits,” Giuliani said in a room of friends and campaign officials three days after the election, hinting at the scope of the alleged voting fraud. Later the same day, in front of Trump and others: “I have 27 affidavits!” And yet again the same day, he urged Trump to put him in charge. “I have 80 affidavits.”

Woodward and Costa have Trump telling advisers that, yes, Giuliani is “crazy,” but “none of the sane lawyers can represent me because they’ve been pressured.”

Lee Holmes, chief counsel for the Trump supporter Senator Lindsey Graham, is portrayed in “Peril” as “astonished at the overreach” of fraud claims by Giuliani and others. Holmes wrote to Graham that the data behind the claims were “a concoction, with a bullying tone and eighth-grade writing.” (Graham disagreed. “Third grade,” he said.)

The note about this book’s sources is nearly identical to the notes in the previous two books. The authors interviewed more than 200 firsthand participants and witnesses, though none are named. Quotation marks are apparently used around words they’re more sure of, but there’s a seemingly arbitrary pattern to the way those marks are used and not used even within the same brief conversations.

And as usual, though the sources aren’t named, some people get the type of soft-glow light that suggests they were especially useful to the authors. In this book, much of that light falls on Milley and William P. Barr, Trump’s attorney general from November 2018 to December 2020.

It was reported when Barr resigned that his relationship with Trump had soured because Barr wouldn’t indulge the president’s belief in election fraud. In “Peril,” that resistance gets fleshed out with some long and pointed speeches suspiciously recalled verbatim. “Your team is a bunch of clowns,” goes part of one of Barr’s confrontations. “They are unconscionable in the firmness and detail they present as if it is unquestionable fact. It is not.”

Milley looks admirable and conscientious if you believe — as Woodward and Costa seem to — that someone needed to surreptitiously work to counteract Trump’s destabilizing effects during the transition of power. (Milley, who remains the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under President Biden, has unsurprisingly taken fire from the right over his reported disloyalty to Trump. Biden has publicly expressed confidence in Milley since the book’s revelations emerged.)

In addition to Milley’s actions, the book has gotten attention for a scene in which — read this next part slowly — the former Vice President Dan Quayle talks sense into Pence. Trump had suggested to Pence that he had the power to essentially rejigger the electoral outcome as head of the Senate, an idea that Quayle told Pence was “preposterous and dangerous.” Woodward and Costa write, in a rare bit of deadpan: “Pence finally agreed acting to overturn the election would be antithetical to his traditional view of conservatism.”

Trump tweeted about the election ballots on the morning they were to be certified: “All Mike Pence has to do is send them back to the States, AND WE WIN. Do it Mike, this is a time for extreme courage!” “Extreme courage” is not the first phrase one reaches for to describe Pence after reading “Peril.”

The vice president talked halfheartedly about election problems in public to stay on Trump’s good side “without going full Giuliani,” Woodward and Costa write. As the certification approached, he asked many lawyers to consider his options. It doesn’t seem he wanted them to empower him as much as he wanted to simply avoid a confrontation with Trump.

On his way to the Capitol on Jan. 6, Pence released a letter saying that he did not have the “unilateral authority” to decide which electoral votes got counted. His reward? About an hour later, protesters inside the Capitol chanted for him to be hanged.

When Trump fired Defense Secretary Mark T. Esper less than a week after the election, Milley saw it, Woodward and Costa write, as part of a “mindless march into more and more disorder.”

The unfortunate truth is that disorder is dramatic. In the wake of the riot, “Peril” loses force. A protracted recounting of security efforts leading up to Biden’s inauguration feels considerably less urgent after the fact. Even more fatally for the book’s momentum, Woodward and Costa devote 20 pages — a lifetime by their pacing standards — to behind-the-scenes negotiations for President Biden’s $1.9 trillion stimulus package. This involves a lot of back and forth with Joe Manchin, the senator from West Virginia whose crucial vote was considered uncertain. Sources may have given Woodward and Costa every detail of these negotiations, but the authors weren’t obligated to use every last one.

The book mounts a final rally, helped by circumstance. In light of recent events, a late section closely recounting Biden’s decision to end the American war in Afghanistan is plenty absorbing. The authors recount Biden’s resistance to the war when he was vice president under Obama: He felt that the addition of 30,000 troops was, Woodward and Costa write, “a tragic power play executed by national security leaders at the expense of a young president.” Biden was long insistent that the point of American engagement in the country was to diminish the threat of Al Qaeda and not to crush the Taliban. He held to his strategy despite advisers who presented him with a “stunning list of possible human disaster and political consequences.”

As “Peril” nears its close, the Delta variant is muddying the pandemic picture, and that’s not the only detail that makes it read like a cliffhanger. “Trump was not dormant,” the authors write. He was staging rallies for supporters, and getting good news about his place in very early polls for 2024. Like an installment of a deathless Marvel franchise, for all its spectacle “Peril” ends with a dismaying sense of prologue.