HOUSTON — The ransomware attack that forced the shutdown of a vital pipeline delivering fuel from the Gulf Coast to the Northeastern United States has caused panic among motorists as thousands of fueling stations have run out of fuel.

The crisis may last only a few days, as most energy experts predict, but it has revealed a disturbing truth: The attack, which the Federal Bureau of Investigation said was carried out by an organized crime group called DarkSide, has highlighted the vulnerability of the American energy system. And the energy the country takes for granted — especially now that it is a major exporter of oil and natural gas — is vulnerable to an attack by a criminal group or hostile country.

While the operator of the Colonial Pipeline has said it hopes to re-establish full service by the end of the week, every day that goes by without fuel will raise gasoline and diesel prices and even threaten the curtailment of air travel.

What’s the latest?

Colonial Pipeline, a private company that has not disclosed much since the breach was discovered late last week, says it is slowly ramping back some local operations. But it has failed so far to give a precise timetable for recovering its operations.

The Biden administration is considering a number of moves, including issuing a waiver for the Jones Act, a century-old law that limits the rights of foreign shipping to move products from one American port to another. The Environmental Protection Agency has already waived some air pollution standards to help alleviate shortages. But no policy can immediately replace a pipeline that ships about 45 percent of the transport fuel used on the Eastern Seaboard.

“There are no easy solutions,” Energy Secretary Jennifer M. Granholm said of her first crisis as a member of the cabinet.

To make matters worse, there is a crisis in confidence.

Drivers in Tennessee, Georgia and several other Southern states are panic-buying, exacerbating shortages with their fears. Motorists have been yelling at one another to move out of the way as they hog pumps to fill up multiple gas cans to hoard.

Several thousand gas stations have run out of fuel, and hundreds of others are limiting sales.

The near hysteria in a few communities has not been seen in years, as some people on social media have begun comparing President Biden to President Jimmy Carter, who was president when gas lines rattled the country after the Iranian revolution and other Middle East troubles.

Experts say the reaction is out of proportion with the actual risk, although there is a possibility that the Colonial Pipeline will not return to full operation by the end of the week.

“The oil and gasoline is there,” said Amy Myers Jaffe, an energy expert at Tufts University. “We can pump it manually, we can carry it by truck, and the government and other entities can hire ships. And we have oil in inventories.”

Officials in states with the longest gas lines are asking for calm. “I’m urging everyone to be careful and be patient,” said South Carolina’s attorney general, Alan Wilson.

What is Colonial Pipeline, and why is the Atlantic Coast so dependent on it?

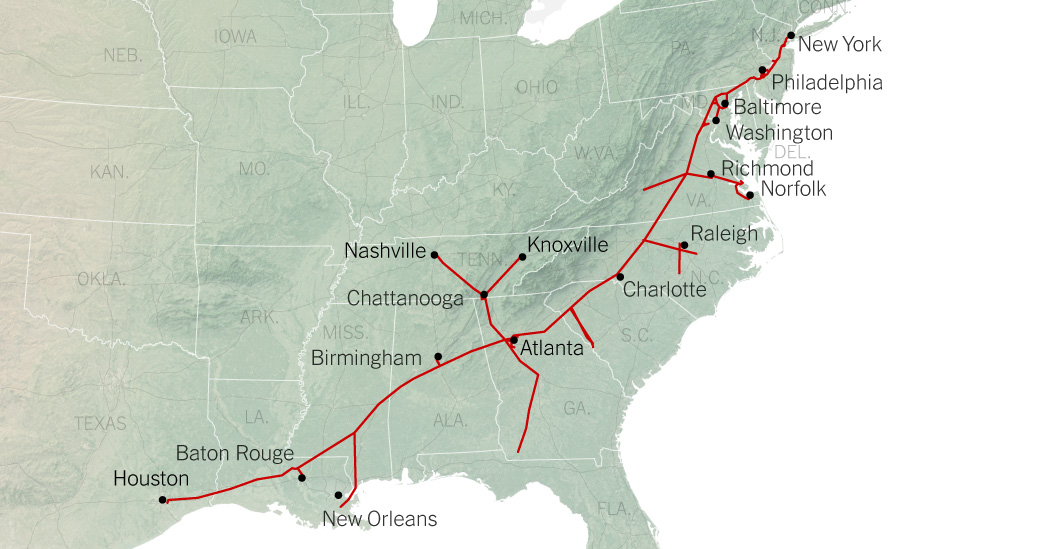

The Colonial Pipeline, based in Alpharetta, Ga., is one of the largest in the United States. It can carry roughly three million barrels of fuel a day over 5,500 miles from Houston to New York. It serves most of the Southern states, and branches from the Atlantic Coast to Tennessee.

Some of the biggest oil companies, including Phillips Petroleum, Sinclair Pipeline and Continental Oil, joined to begin construction of the pipeline in 1961. It was a time of rapid growth in highway driving and long-distance air travel. Today Colonial Pipeline is owned by Royal Dutch Shell, Koch Industries and several foreign and domestic investment firms.

It is particularly vital to the functioning of many Eastern U.S. airports, which typically hold inventories sufficient for only three to five days of operations.

There are many reasons it has become so vital, including regulatory restrictions on pipeline construction that go back nearly a century. There are also restrictions on road transport of fuels.

But the main reason comes closer to home. Over the last two decades, at least six refineries have gone out of business in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Virginia, reducing the amount of crude oil processed into fuels in the region by more than half, from 1,549,000 to 715,000 barrels weekly.

“Those refineries just couldn’t make money,” said Tom Kloza, global head of energy analysis at Oil Price Information Service.

The reason for their decline is the “energy independence” that has been a White House goal since the Nixon administration. As shale exploration and production boomed beginning around 2005, refineries on the Gulf Coast had easy access to natural gas and oil produced in Texas.

That gave them an enormous competitive advantage over the East Coast refineries that imported oil from abroad or by rail from North Dakota once the shale boom there took off. As the local refineries shut their doors, the Colonial Pipeline became increasingly important as a conduit from Texas and Louisiana refineries.

The Midwest has its own pipelines from the Gulf Coast, but while the East Coast closed refineries, the Midwest has opened a few new plants and expanded others to process Canadian oil, much from the Alberta oil sands, over the last 20 years. California and the Pacific Northwest have sufficient refineries to process crude produced in California and Alaska, as well as South America.

How serious is the threat, and what happens now?

Attacks on critical infrastructure have been a major concern for a decade, but they have accelerated in recent months, raising concerns that basic services like heat, light and transportation can be threatened and stopped in an instant by shadowy criminal groups that sometimes have tacit or active support from foreign governments.

When infrastructure is bombed it is an act of war, but when it is hobbled by a computer virus what is it exactly? Sometimes such viruses are even hard to trace.

The current pipeline problem is serious for its implications on national security even though Northeast fuel supply system is flexible and resilient.

Many hurricanes have damaged pipelines and refineries on the Gulf Coast in the past, and the East Coast was able to manage. The federal government stores millions of gallons of crude oil and refined products for emergencies. Refineries can import oil from Europe, Canada and South America, although trans-Atlantic cargo can take as much as two weeks to arrive.

When Hurricane Harvey hit Texas in 2017, damaging refineries, Colonial Pipeline shipments to the Northeast were suspended for nearly two weeks. Gasoline prices at New York Harbor quickly climbed more than 25 percent, and the added costs were passed on to motorists. Prices took over a month to return to previous levels.

Hurricanes come and go. But this crisis is different. Federal investigators said the attackers aimed at poorly protected corporate data.

Colonial Pipeline stopped shipments apparently as a precaution to prevent the hackers from doing anything further, like turning off or damaging the system itself in the event they had stolen highly sensitive information from corporate computers.

Colonial said it was reviving service of segments of the pipeline “in a stepwise fashion” in consultation with the Energy Department. It said the goal of its plan was “substantially restoring operational service by the end of the week.” The company cautioned, however, that “this situation remains fluid and continues to evolve.”

The group responsible for the pipeline attack, DarkSide, typically locks up its victims’ data using encryption, and threatens to release the data unless a ransom is paid. Colonial Pipeline has not said whether it has paid or intends to pay a ransom.

Several governors have declared states of emergency in the last few days to try to contain the growing crisis, including Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida, who activated the state’s National Guard on Tuesday evening. President Biden, officials say, has been deeply involved in the daily management of the crisis. It is the first time during his administration that a ransomware attack has caused such a significant shutdown, and it is an episode he sees as a vivid illustration of the failing state of American infrastructure — the focus of his spending proposals in Congress.

“The unfortunate truth is that infrastructure today is so vulnerable that just about anyone who wants to get in can get in,” said Dan Schiappa, chief product officer of Sophos, a British security software and hardware company. “Infrastructure is an easy — and lucrative — target for attackers.”

David E. Sanger contributed reporting.