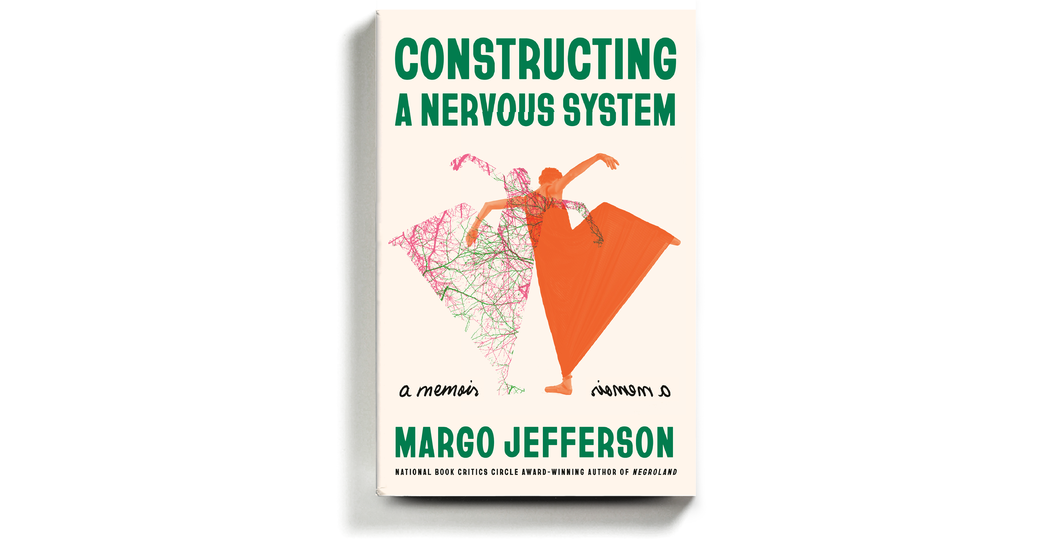

CONSTRUCTING A NERVOUS SYSTEM

A Memoir

By Margo Jefferson

197 pages. Pantheon Books. $27.

If Margo Jefferson had gone into another profession — cabinetmaking, let’s say — she’d be the type to draw and redraw plans for a cabinet, build and tinker with the cabinet, stand back to look at the cabinet from every angle, probe the purpose of woodworking, take a break to go examine 2,000 other cabinets, then disassemble her own product and start from scratch with alternative tools, creating an object that no longer resembled a cabinet but performed all the functions of one in startling ways.

Jefferson is a Pulitzer Prize-winning critic, not a cabinetmaker (that I know of), but this is the spirit in which her second memoir, “Constructing a Nervous System,” proceeds. Her experiment is instantly effective.

The book is a companion to Jefferson’s first memoir, “Negroland,” which won a National Book Critics Circle Award in 2016. “Negroland” told the story of growing up amid the Black bourgeoisie of Chicago; Jefferson’s father was a prominent doctor and her mother a fashionable socialite. Margo and her sister, Denise, were sent to ballet class and kitted up in matching wool coats with Persian lamb collars; they mastered orthopedically correct posture and crisp speech. Poise, poise, poise.

In “Negroland,” Jefferson asked: “What has made and maimed me?” Her new book begins by cross-examining what that “me” consists of, posing the question of how to author a memoir when you chafe against the concept of authority. Two solutions come to mind. One, go mad. Two, redraw the boundaries of the genre. Jefferson selects Option 2, and the book’s title is a sly description of the project, with “nervous system” referring not to anatomical fibers and cells but to the materials — “chosen, imposed, inherited, made up” — that jumble together into an identity. And that may, with skill, be coaxed into a narrative.

A quick flip through the pages might set off alarm bells for those fearful of italics, bold type, capital letters, dictionary definitions and chunky quotations. But this is a book for deep submergence, not quick flipping. This is appointment reading. Clear the schedule and commit.

Issuing commands like the above is one of Jefferson’s techniques. “Read on,” she orders at one point. At another, discussing Bud Powell, she insists: “Don’t pity him.” She writes in the first and second person — and also, because why not, in the voice of Bing Crosby. She borrows the conceit of a forensic procedural to investigate Willa Cather’s work. There are letters, calls to action, song lyrics, aphorisms, annotations, unearthed journal entries, a theory of minstrelsy. There are excerpts from Charlotte Brontë, Katherine Mansfield, Ida B. Wells, Czeslaw Milosz; allusions to Beckett, Robert Louis Stevenson and Dante.

It takes a strong sensibility to make all of this jump-cutting not only coherent but hypnotic. Jefferson’s sensibility is one of exquisitely personal engagement with art. Yes, part of the book is a hypertextual rumination on the nature of memoir, and there is a dusting of traditional autobiography — she writes about her father’s depression, her teaching career, a love affair — but in the dance between autobiographer and critic, the critic is leading.

Early in the book, Jefferson recalls retrieving a handful of Ella Fitzgerald records from her parents’ collection. Having been raised to exalt physical impeccability, a preteen Jefferson was squeamish at the sight of Fitzgerald’s “sweat and size” on album covers and TV appearances. She couldn’t reconcile the voice’s version of femininity with the fact that Fitzgerald possessed functional sudoriferous glands. In revisiting her own discomfort, Jefferson expounds on the relationship between Black women and sweat, labor and glamour.

These encounters with artists — Powell, Josephine Baker, Harriet Beecher Stowe and beyond — are ravishing and rigorous, but they are interrupted with fretting and self-admonishment. “I’ve reached an emotional stalemate here,” Jefferson writes, and “This confessing and reckoning have exhausted me” and “STOP! Collect yourself, Professor Jefferson.” A drill sergeant has infiltrated the nervous system.

Coming upon one of these sentences is a jolt of unexpected intimacy, like glancing across the street and seeing a neighbor wander naked past the window. In “Negroland,” Jefferson wrote about the semiotics of self-presentation — how an unmoisturized elbow or knee signaled deficiency, while a closet full of occasion-specific pocketbooks stood for irreproachable preparedness. Her jittery bursts energize a writing style that is similarly meticulous.

I hesitate to ascribe Jefferson’s examined self-consciousness entirely to gender or race or class. All of those ingredients matter a great deal, but it is also true that some people are born self-conscious and some people become that way, while others never do. (We all know specimens of that supernatural anomaly, the self-assured human.) I say this not to obscure the specificity of Jefferson’s life — the expression of which is the point of any memoir — but to situate it in an artistic tradition that includes Emily Dickinson, Frida Kahlo and Ingmar Bergman: ruthless self-excavation that is scrupulously free of solipsism.

Jefferson writes about craving “license” as a young woman, dispensation to play “with styles and personae deemed beyond my range.” She has — along with other recent innovators in the form, like Carmen Maria Machado, Joy Harjo and Maggie Nelson — grabbed hold of that permission slip and torn it to shreds.