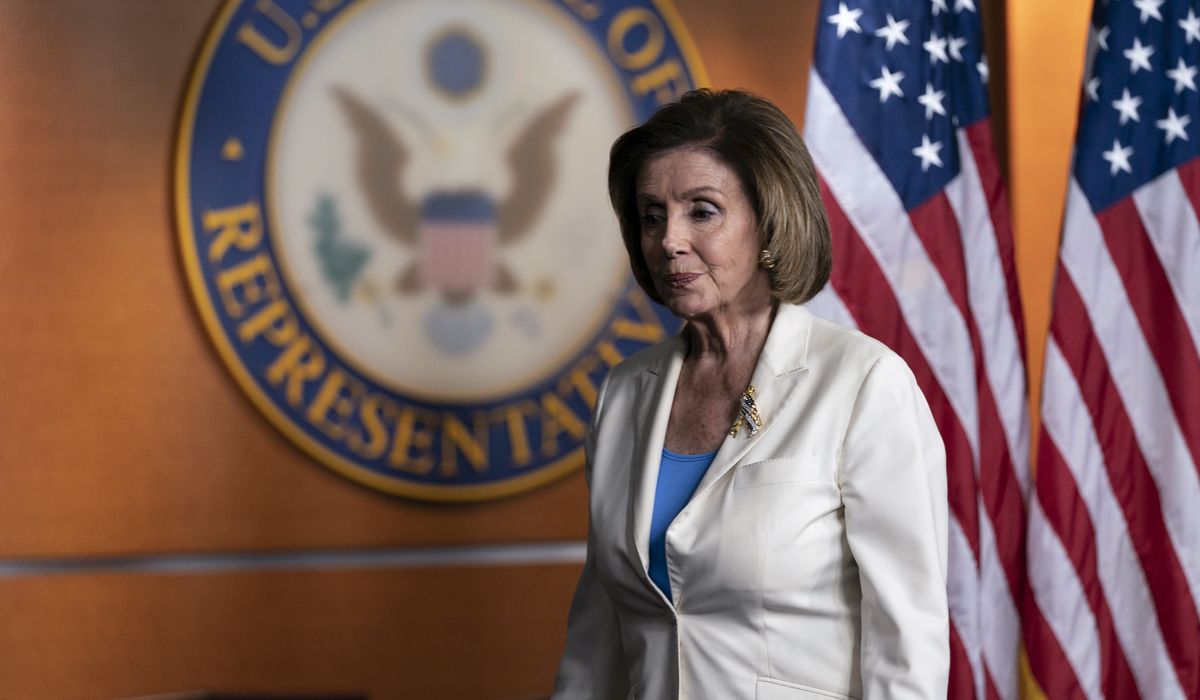

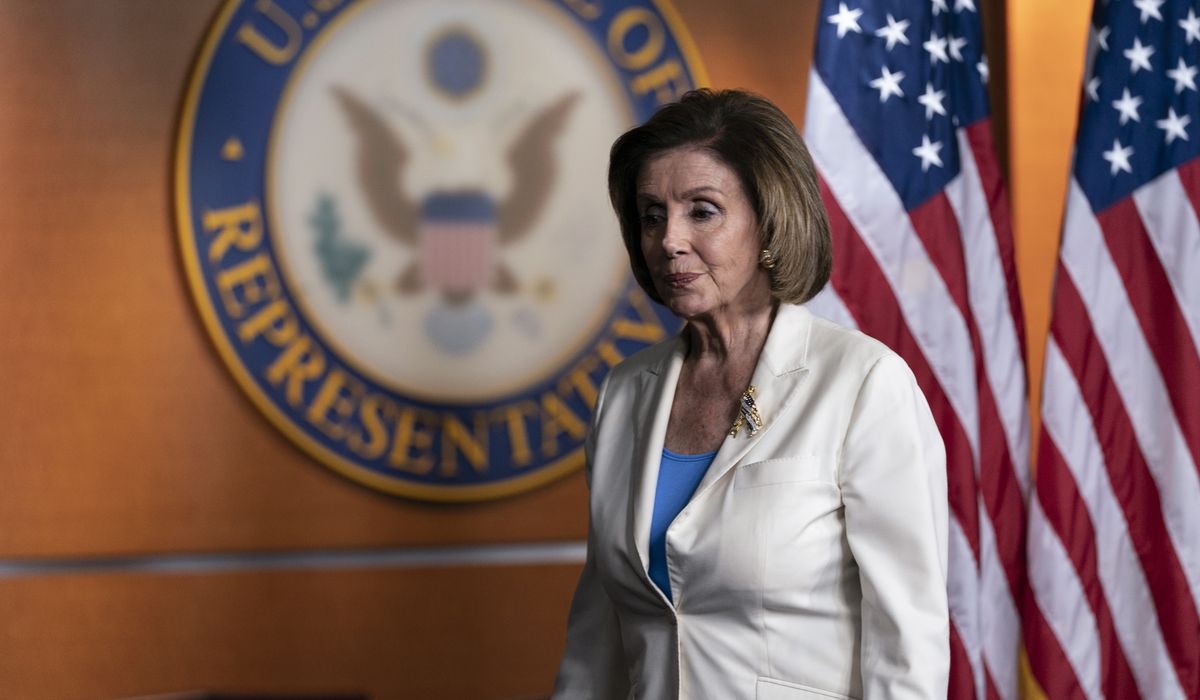

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi vowed on Thursday to block any infrastructure package until the Senate passed, along party lines if necessary, a “human infrastructure” package filled with liberal priorities such as job training for felons and new climate change regulations.

“Let me be really clear on this: we will not take up a bill in the House until the Senate passes the bipartisan bill and a reconciliation bill,” the California Democrat said. “If there is no bipartisan bill, then we’ll just go when the Senate passes a reconciliation bill.”

The remarks came shortly before a group of 21 senators met with President Biden at the White House and reached a tentative deal on the public works package. Earlier this week, the group agreed to a tentative “framework” after meeting with senior members of the administration’s domestic policy team.

A White House summary of the proposal indicates $1.2 trillion would be spent over eight years. Of that sum, more than $579 billion would come from new revenue sources such as narrowing the “tax gap,” or the difference between taxes owed and taxes paid.

Lawmakers estimate they can net more than $100 billion by boosting the IRS’s enforcement standards.

Funding for the deal also would come from repurposing $125 billion in unused coronavirus relief funds. Similarly, federal unemployment insurance that was rejected by state governments because of tight labor markets would be repurposed.

Much to the chagrin of the far-left, however, the package focuses exclusively on conventional infrastructure. Of the package’s $1.2 trillion total, $579 billion goes to upgrading the nation’s roads, bridges and other transportation systems.

While it does include $7.5 billion for deploying electric vehicle charging stations, the package is significantly more narrow than the initial $2.3 trillion Mr. Biden had proposed.

Progressives argue that Democrats should not give up on a larger package that includes both “hard” infrastructure, such as upgrades to the nation’s transportation systems, and social welfare and climate change spending.

As such, they have pledged to oppose the bipartisan deal unless a guarantee is given that non-infrastructure-related spending will be pushed through separately via the budget reconciliation process. The process allows spending bills to pass the Senate with a simple majority of 51 votes, overcoming any Republican filibuster.

“I’m hopeful that we would have a bipartisan bill. I think it would be really important to demonstrate the bipartisanship that has always been a hallmark of our infrastructure legislation,” Mrs. Pelosi said. “But we’re not going down the path unless we all go down the path together.”

Mr. Biden backed up the speaker during a press event at the White House on Thursday announcing the infrastructure deal.

“If this is the only one that comes to me, I’m not signing it,” he said. “It’s in tandem … I’m not just signing the bipartisan bill and forgetting about the rest that I proposed.”

The problem, however, is that to secure a commitment on reconciliation, all 50 Democrats are needed.

It is not clear whether that will be possible. Centrist Democrats, including Sens. Joe Manchin III of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, are taking a wait-and-see approach.

“This is no surprise to anyone, but I’m always committed to working with anyone to get things done,” Ms. Sinema said.

Even so, few expect the moderates would line up behind a multi-trillion dollar reconciliation package like that being pitched by Senate Budget Committee Chairman Bernard Sanders, a self-described socialist from Vermont. Mr. Sanders has called for a package topping $6 trillion that prioritizes job retraining for felons and climate change.

Instead, centrists are eyeing a scaled-down reconciliation bill that focuses on workforce development and family incentives.

“Reconciliation is inevitable,” Mr. Manchin said. “We just don’t know what size it’s going to be.”

It is not clear, though, if just any bill would be enough to pacify Mrs. Pelosi. As House speaker, she has significant power over which legislation comes to the floor and when. Without Mrs. Pelosi’s backing, the bipartisan infrastructure package is likely dead in the House.

“She drew a red line,” said one Democratic House aide. “Over here, that means everything.”

Several lawmakers on Thursday questioned whether Mrs. Pelosi’s public gambit was necessary as Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer had already pledged a “two-track” approach on infrastructure.

“I would have hoped we trusted each other a little more than that,” said Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, a New Hampshire Democrat and one of the authors of the bipartisan deal. “But I appreciate that there are those who feel like there is an opportunity to get other pieces of the president’s plan into another bill.”