We learn about Jimena, Liselle’s “helper,” who is supposed to assist with the party but sends her daughter, Xochitl, instead. Liselle can’t pronounce Xochitl’s name, and feels awkward ordering the younger woman — a Ph.D. student and immigration rights activist — to defrost mushroom tarts. For that matter, she also feels awkward paying Jimena, an old woman with bad knees, to scrub her bathroom and load her dishwasher. Contemplating the employees, she pictures herself as “the Black mistress of a tiny plantation” or “wearing a hoopskirt and waving her lace fan at Xochitl, across a gulf, from the wrong side of history.” Then again, Liselle doesn’t want to scrub the bathroom herself.

Her thoughts always return to Selena. Where Liselle has scrambled up the socioeconomic ladder and now plays gracious hostess to the “menacingly dull” lawyers at Winn’s firm, Selena lives with her mother and works two jobs. She wears a raggedy sweatshirt. Her boss at one job tells her that she is “a 3-D Black person trying to fit into a 2-D box.” Her primary duty is to maintain chemical stability; her routine consists of work, medication, therapy, peppermint tea, sleep, repeat. When Liselle calls and leaves a message with Selena’s mother, Selena’s carefully tended equilibrium is dashed.

A running theme of the novel is the misidentification of Liselle, both by others and herself. Nobody can get her name right. Some people call her “Liesl” and others “Lysol”; her grandmother-in-law goes with “Lisa” while her mother-in-law, slightly closer to the mark, lands on “Lisette.” The very question that prompts the phone call is whether Liselle, when she gave up Selena, surrendered the possibility of recognition for good. As a young woman she dated girls and read Audre Lorde and earned a reputation as an icy seductress. At 41 she is afraid of her mom, annoyed by her friends, insecure about her thinning hairline. Worst of all, she has adopted the politician’s habit of referring to people as “folks.”

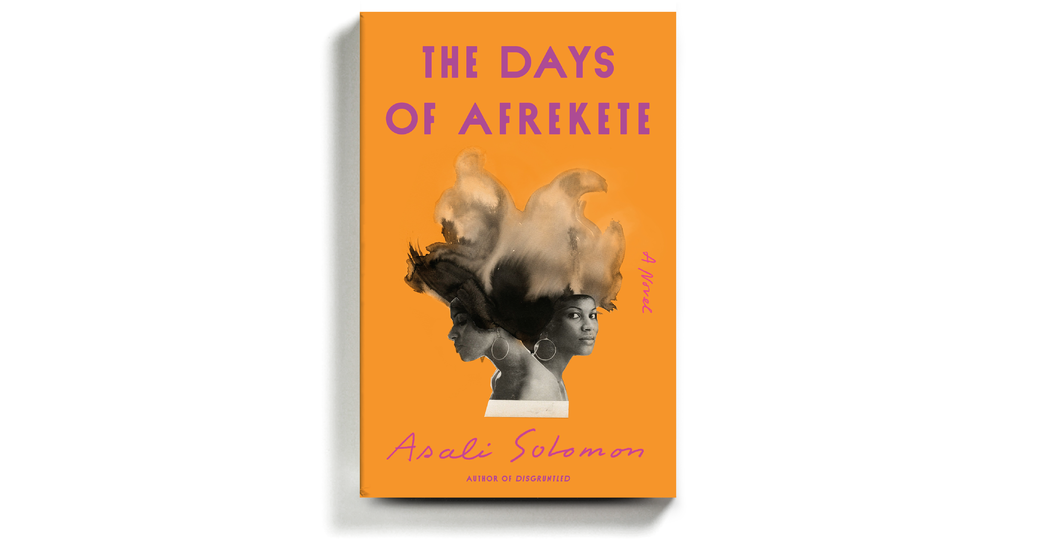

Liselle’s call to Selena happens in the first few pages of the book, just before dinner begins, which is to say that we meet our protagonist at the precise moment her Potemkin life becomes intolerable. What exactly the gesture triggers is revealed over the course of a novel so concise it reminded me of one of those wrinkle-free travel dresses that magically expand from a folded cube into a wearable garment. Solomon’s novel is a feat of engineering. It’s also a reverie, a riff on “Mrs. Dalloway” and a love story. In Liselle, Solomon has invented a character who comes to the mind’s eye in HD, with anxieties, jokes, memories, furies and survival instincts all present in prose as clear as water.