One New York night in the early 1970s, a dancer and budding filmmaker named Wakefield Poole went to see a gay porn flick called “Highway Hustler” at a run-down theater in Times Square with his friends. As he settled into a tattered seat, he prepared to spend the next 45 minutes or so enjoyably aroused.

But as the film rolled, he experienced nothing of the kind. He thought that the movie was sleazy, that its sex scenes were unnecessarily degrading. He started laughing out loud, and one of his companions fell asleep.

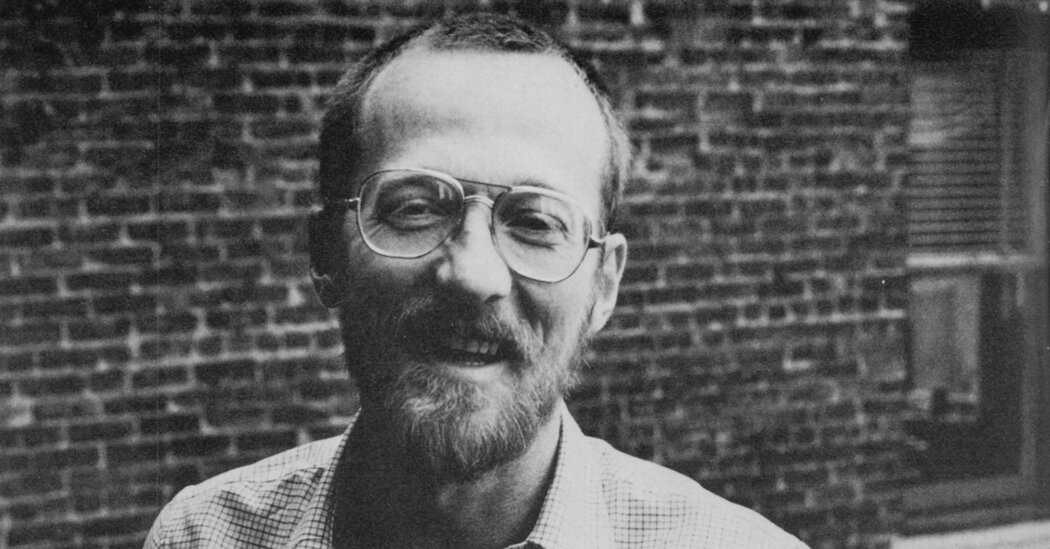

“I said to my friend, ‘This is the worst, ugliest movie I’ve ever seen!’” Mr. Poole, who died on Oct. 27 at 85, recalled in 2002. “Somebody ought to be able to do something better.”

The Stonewall uprising in Greenwich Village had occurred two years earlier, and Mr. Poole, like countless gay men of his generation, was empowered in its aftermath. What he had witnessed onscreen that night didn’t resemble the sexual liberation he was experiencing as a proud gay man in New York.

Thus, armed with a 16-millimeter Bolex camera, Mr. Poole decided to do something about it. He headed to Fire Island Pines, the secluded summer Eden for gay men just off Long Island, and there began filming experimental movies with his friends, capturing them making love on beaches and in shady groves.

And he did so with an auteur’s touch, as if he were some horny version of D.A. Pennebaker, striving to portray artful realism in the male intimacy he was documenting.

Mr. Poole soon made a feature-length, surrealistic movie called “Boys in the Sand” (the title a spoof on “The Boys in the Band,” the groundbreaking 1968 play and 1970 film adaptation about gay men in New York), and its release in 1971 proved revelatory. He was hailed as a pioneer of gay porn, and the film became a crossover hit that changed attitudes about pornography among both the gay and straight audiences that lined up to see it.

The movie, with the adult film star Casey Donovan, was composed of three steamy vignettes: First, Mr. Donovan materializes from the ocean Venus-like to ravage a young man lying on the sand; then, at a beach house, he tosses a dissolving magic pill into a swimming pool, causing a hunk to emerge from the water; lastly, he pleasures himself while admiring a telephone line repairman working outside his window.

When “Boys in the Sand” opened at the now gone 55th Street Playhouse in Manhattan, it became the talk of the town. The sex it portrayed between Adonic men frolicking in the Pines came across to viewers as blissful and guilt-free. Soon, celebrities like Liza Minnelli, Rudolf Nureyev and Halston were also lining up to see it.

“I wanted a film,” Mr. Poole said at the time, “that gay people could look at and say, ‘I don’t mind being gay — it’s beautiful to see those people do what they’re doing.’”

In a memoir, “Dirty Poole,” published in 2000, he related how, during the film’s release, its producer sneakily bought an ad for the film in The New York Times, leading Mr. Poole to speculate that the paper’s advertising department may not have looked at it too closely. Variety reviewed the movie, a rare instance of critical coverage of hard-core gay pornography by a mainstream publication (though it took a dim view of the movie). Even the film’s marquee billing challenged precedent: It displayed Mr. Poole’s real name.

While “Boys in the Sand” marked Mr. Poole’s official debut as a filmmaker (he had made some experimental short films earlier), his first passion was dance: He had led an impressive career performing in the New York-based company Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo and helping with the choreography of Broadway shows involving the likes of Richard Rodgers, Stephen Sondheim and Noël Coward.

“There weren’t a lot of people who were out,” Mr. Poole told South Florida Gay News in 2014. “Just seeing my name above the title on a theater made its impact. Hundreds of people saw ‘Boys in the Sand’ and came out after seeing the film.”

The year after “Boys” appeared, the landmark film “Deep Throat” was released, commencing a golden age of American pornography. “Wakefield was determined to elevate the gay porn genre,” Michael Musto, the longtime Village Voice writer, said in a phone interview. “This was a time when you had to leave your home to see pornography. It was a communal experience by necessity, and you had to be seen in your seat. He removed the shame of it.”

Mr. Poole’s next hit, “Bijou,” followed a construction worker who stumbles on an invitation to a private club, where he joins a psychedelic bathhouse-style orgy. Then came “Wakefield Poole’s Bible!,” a creatively ambitious soft-porn movie that reimagined tales from the Old Testament, but it flopped.

Frustrated with its failure, Mr. Poole started afresh in San Francisco, which had become an epicenter of the gay rights movement, although his troubles only worsened there: He broke up with his longtime partner, and he became addicted to freebasing cocaine.

He soon directed a documentary-like film, “Take One,” in which he interviewed men about their carnal fantasies and had them act them out on camera, in one notorious moment engaging two brothers.

Mr. Poole eventually moved back to New York, holing himself up in a cold-water flat in Chelsea to break his cocaine addiction. Trying for a comeback, he released “Boys in the Sand II” in 1984, but it didn’t make a splash.

The AIDS crisis had begun, and the carefree gay paradise depicted in his original movie suddenly felt a world away.

“The reason I stopped making films was the AIDS situation,” Mr. Poole told an interviewer. “I lost my fan base to AIDS. I saw them all die. It’s a miracle I’m not dead. Cocaine saved my life. I did so much coke, I couldn’t have sex.”

Walter Wakefield Poole III was born on Feb. 24, 1936, in Salisbury, N.C. His father was a police officer and later a car salesman. His mother, Hazel (Melton) Poole, was a homemaker.

Growing up, Walter fell in love with a boyhood friend, and they would crawl through each other’s window to be together. But their romance ended when Walter’s family moved to Florida, settling in Jacksonville. Years later, he said, after his friend had married a woman and started a family, they rekindled their passion one night.

Walter caught the dance bug in Jacksonville and started studying ballet seriously. When he was 18, he headed to New York to pursue dance further and joined the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo when he was 21.

He turned to moviemaking in the 1960s, captivated by the experimental films of Andy Warhol.

As he pulled away from pornography in the mid-1980s, Mr. Poole needed to find a new way to make a paycheck in New York, so he studied at the French Culinary Institute and later landed a job in food services for Calvin Klein.

He retired in his 60s and moved back to Jacksonville, where he died in a nursing home, a niece, Terry Waters, said. He left no immediate survivors.

As Mr. Poole grew older, enthusiasts of gay history and vintage pornography collectors began revisiting his work. A documentary, “I Always Said Yes: The Many Lives of Wakefield Poole,” directed by Jim Tushinski, came out in 2016. New York art house theaters like Metrograph and Quad Cinema screened “Boys in the Sand.”

In 2010, Mr. Poole, then 74, was invited to the Pines for a screening of his classic, although some gay residents there weren’t thrilled about it.

A local film festival, responding to their complaints about the X-rated content, had declined to show the movie, so an opposing faction of residents organized their own event. Their group included a man who lived in a summer house that had been used in the film.

That night, Mr. Poole was introduced to a packed auditorium as an unsung hero who had helped transform the Pines into an international destination. (“Boys in the Sand” was seen widely overseas.) He took the stage to applause.

“What has happened here with the controversy is why I made this film,” he told the crowd. “It’s the ultimate of what I wanted this film to do, and that’s to not only make controversy, but to overcome controversy.”

He added: “When I first came to Fire Island, I felt free for the first time in my life. I didn’t feel like a minority and I wanted everybody to suddenly feel that. So I said, ‘I can make a movie that no one will be ashamed to watch.’”