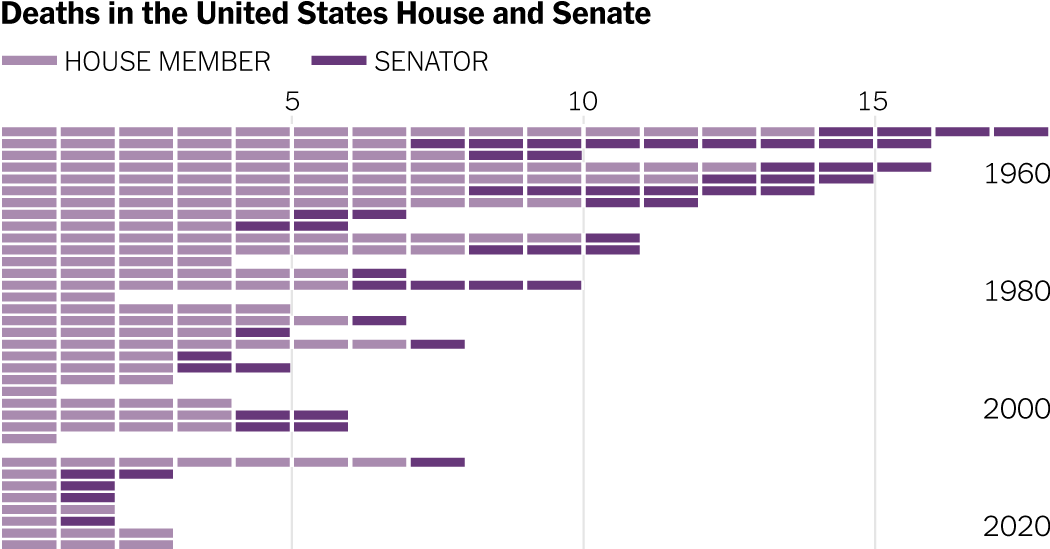

In the House this term, deaths have already affected the parties’ close margins. Three members — Ron Wright of Texas and Representative-elect Luke Letlow of Louisiana, both Republicans; and the Democrat Alcee Hastings of Florida — have died, the most in a Congress in its first three months since the early 1980s. (Mr. Wright and Mr. Letlow died from Covid-19.)

Health problems have also dogged the Senate. Patrick Leahy, 81, Democrat of Vermont, was briefly hospitalized in January. Thom Tillis, 60, a North Carolina Republican, underwent cancer treatment. Questions have been raised about the health of Dianne Feinstein, 87, a Democrat who has represented California since 1992. Vermont’s other senator, Bernie Sanders, 79, had a heart attack in 2019.

In the most extreme case, deaths could end Democrats’ ability to pass legislation without Republican support — or even flip control of either chamber. That’s more likely in the evenly divided Senate, where a single Democratic vacancy could hand Republicans committee gavels and the power to schedule votes until a Democratic successor was appointed or elected.

A serious illness could also upset the party’s delicate legislative arithmetic. “Schumer needs all 50 votes,” said Mr. Fallon, now the executive director of Demand Justice, a progressive advocacy group focused on the federal judiciary. “If somebody is laid up or is hospitalized for a long period of time and their vote’s not there, then having the majority is somewhat meaningless.”

It’s also possible that a special election or governor’s appointment could shift Senate control more lastingly. Several states require governors to fill vacancies with a temporary replacement of the same political party as the departed senator. But nine senators in the Democratic caucus represent states with Republican governors who can appoint anyone they choose. That could let a Republican governor name a Republican replacement, giving Republicans the majority, even if it may be temporary. (Six Republican senators represent states with Democratic governors who have similar authority.)

House vacancies are filled by special election, and relatively few seats are competitive, lowering the chances that deaths could alter partisan control. No special election to Congress so far this year has flipped a seat.

But special elections take time to organize; delays could further shrink Democrats’ single-digit margin for error. Though House control has never changed mid-session, Republicans could push to elect a new speaker and take over committees if vacancies forced Democrats below a majority of seats, said Sarah Binder, a George Washington University political scientist who has studied congressional deaths.