In the Mukilteo School District in Washington State, the school board voted to remove “To Kill a Mockingbird” — voted the best book of the past 125 years in a survey of readers conducted by The New York Times Book Review — from the ninth-grade curriculum at the request of staff members. Their objections included arguments that the novel marginalized characters of color, celebrated “white saviorhood” and used racial slurs dozens of times without addressing their derogatory nature.

While the book is no longer a requirement, it remains on the district’s list of approved novels, and teachers can still choose to assign it if they wish.

In other instances, efforts to ban books are more sweeping, as parents and organizations aim to have them removed from libraries, cutting off access for everyone. Perhaps no book has been targeted more vigorously than “The 1619 Project,” a best seller about slavery in America that has drawn wide support among many historians and Black leaders and which arose from the 2019 special issue of The New York Times Magazine. It has been named explicitly in proposed legislation.

Political leaders on the right have seized on the controversies over books. The newly elected governor of Virginia, Glenn Youngkin, a Republican, rallied his supporters by framing book bans as an issue of parental control and highlighted the issue in a campaign ad featuring a mother who wanted Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” to be removed from her son’s high school curriculum.

In Texas, Governor Greg Abbott demanded that the state’s education agency “investigate any criminal activity in our public schools involving the availability of pornography,” a move that librarians in the state fear could make them targets of criminal complaints. The governor of South Carolina asked the state’s superintendent of education and its law enforcement division to investigate the presence of “obscene and pornographic” materials in its public schools, offering “Gender Queer” as an example.

The mayor of Ridgeland, Miss., recently withheld funding from the Madison County Library System, saying he would not release the money until books with L.G.B.T.Q. themes were removed, according to the library system’s executive director.

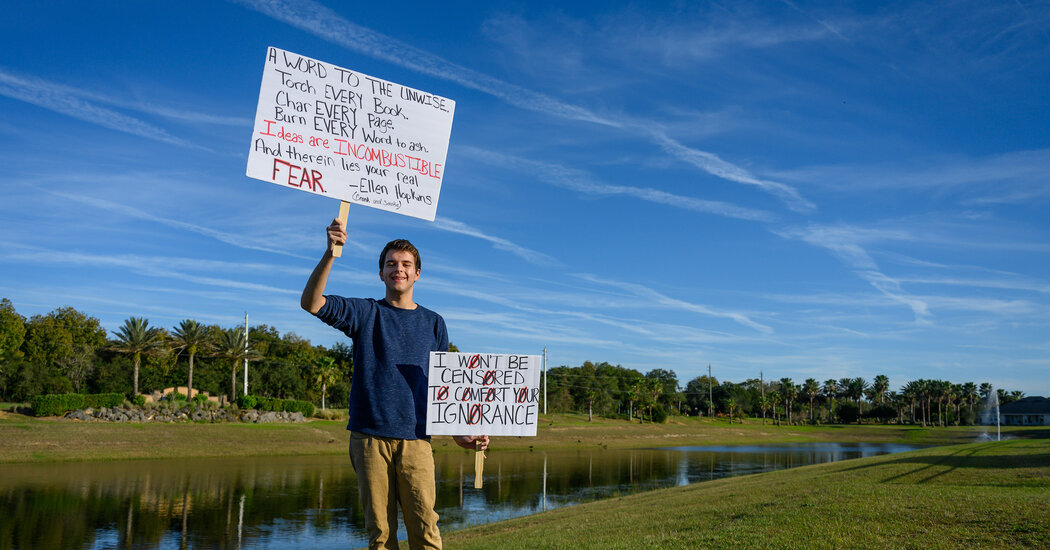

George M. Johnson, the author of “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” a memoir about growing up Black and queer, was stunned in November to learn that a school board member in Flagler County, Fla., had filed a complaint with the sheriff’s department against the book. Written for readers aged 14 and older, it includes scenes that depict oral and anal sex and sexual assault.